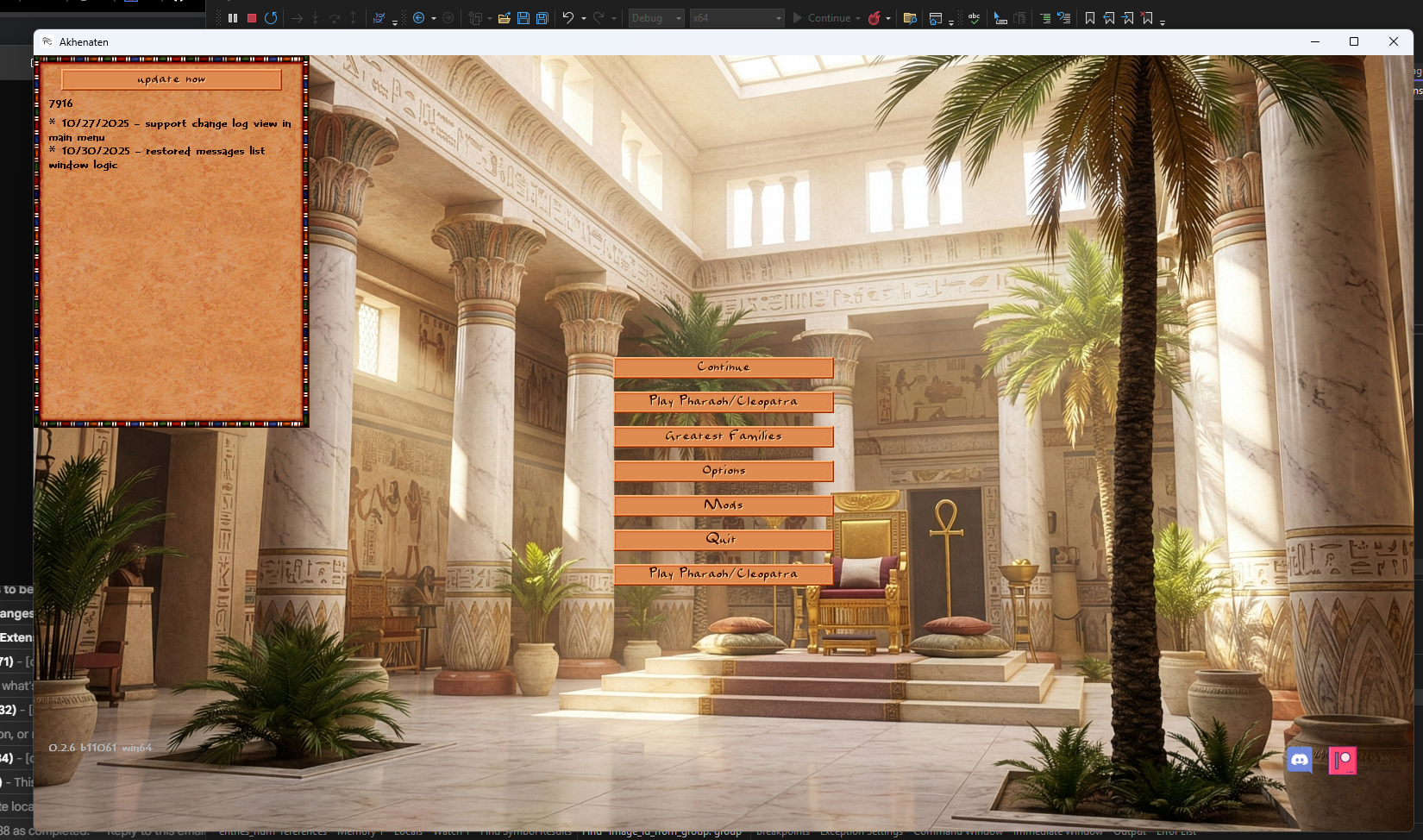

Changes in Akhenaten for 2025

Main Development Directions

Major Architecture Refactoring

Transition to Configuration System

Massive migration of logic from C++ to JavaScript configs

All buildings and figures are now configured through JS configs

Simplified data loading system from archives

New scheme for registering enum tokens in JS

Unified system for loading structures from configs

Refactoring of Building and Figure Classes

Extraction of runtime_data from common building class into specialized classes

Migration of planner logic into building classes

Simplification of type casting system for buildings and figures

Reorganization of figure system with base class extraction

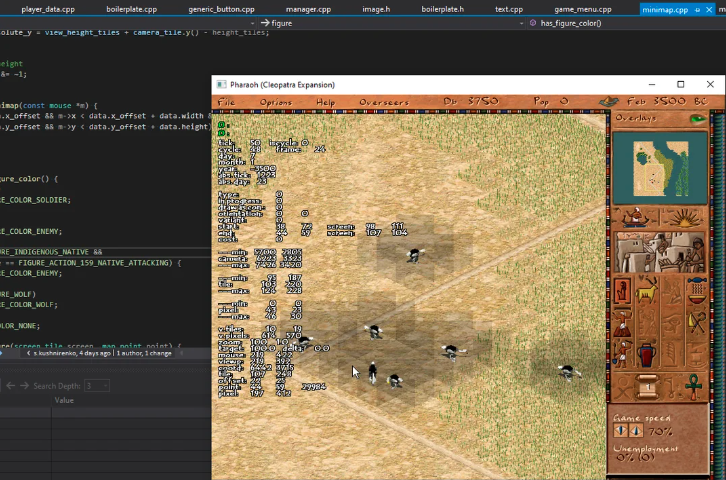

Enemy and Invasion System

New Enemy System

Added enemy figure types (barbarian, hittite, hyksos, kushite, persian, roman, phoenician, nubian, libian, assyrian, seapeople)

Battalion system (batalions) instead of legions

Improved enemy army formation logic

Invasion points system with support for sea and land invasions

Enemy properties configuration through configs

Enemy strength grid system

Improved archer logic

Distant battle system

Debug window for enemy armies

City siege event handling

New Language Support

Added German language support

Added Spanish language support

Migration of all localizations from C++ to JS configs

Improved font system with Unicode support

Tools for generating game fonts

Loading localizations from .sgx archives

Support for external language directories

Improved Unicode font rendering

New Building Types

Carpenter Guild with carpenter figure

Stonemasons Guild with stonemason figure

Tower Gatehouse

Improved logic for Senet House

Restored logic for Carpenter Guild

Irrigation canals system with improved logic

Garden system with decay logic

Improved logic for Temple Complex

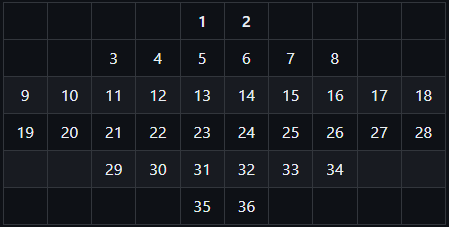

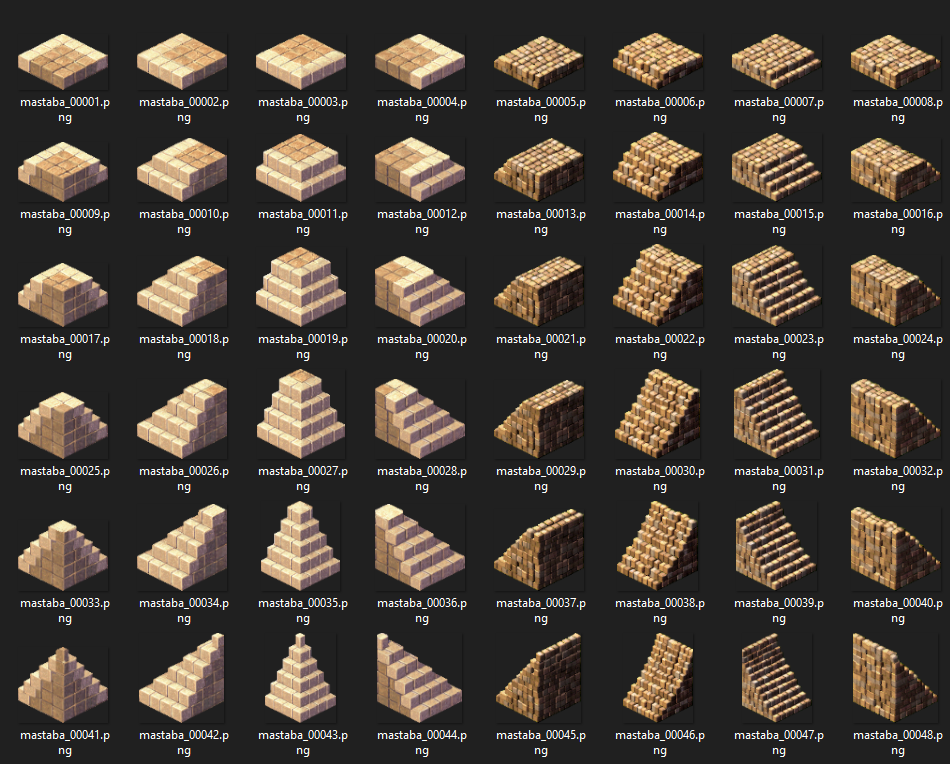

Mastaba system with static parameters support

Resource Depletion System

Implemented depletion system for all quarry types

Resource depletion for copper mines

Depletion system for gems

Save/load resource state (copper, stone, gems grids)

New city_resource_handle class for simplified resource handling

Improved resource storage logic in buildings

Mission resource configuration through configs

UI/UX Improvements

Information window for trade caravans and ships

Information window for gatehouse

Information window for forts and legions with formation mode buttons

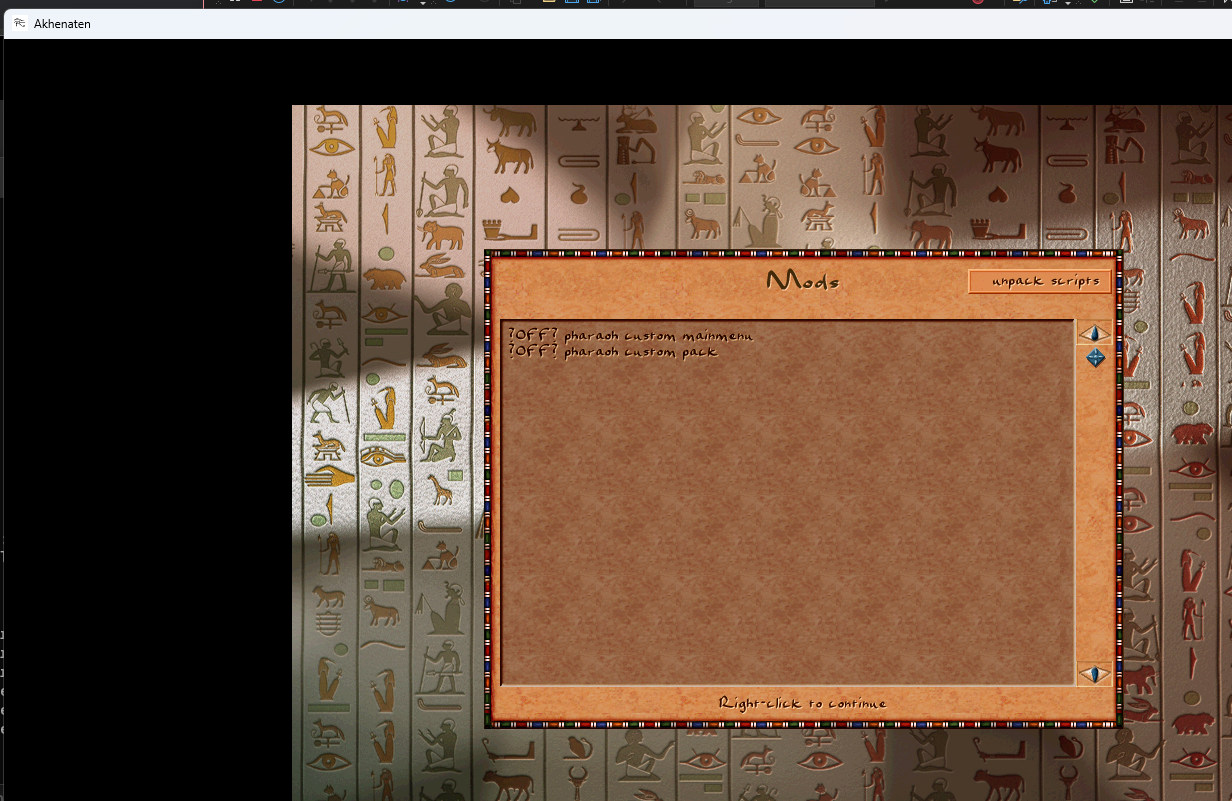

Mod manager window

Event history window

Political overseer window

Fixed top menu when resizing window

Improved scrollbar system

Dynamic text support for buttons

Improved tooltips for buildings and figures

Image centering support in messages

Improved mission window

Graphics Improvements

New deferred rendering system with Y-sorting

Improved cart rendering

Grayscale support for images

Cloud system with settings

Improved isometric texture rendering

Texture caching for performance improvement

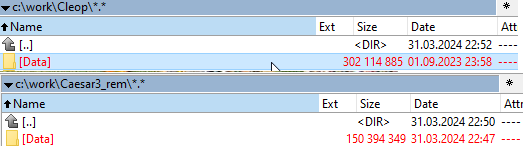

Mod Support

Ability to download mods from GitHub

Save/load active mods

Texture loading support from modpacks

Improved data loading from .sgx archives

Automatic start index detection for images

Technical Improvements

- Build support for Bazzite Linux

- Build improvements for macOS (ARM and x86)

- Build improvements for Android

- Fixes for Emscripten/WASM

- System libpng support on macOS

Architectural Improvements

New type system (typeid implementation)

stable_array class for hash-sorted arrays

Improved variants system

New events system

Improved routing system with amphibian support

Empire System

Trade and Empire Improvements

Empire system redesign using handles instead of raw numbers

Improved trade route logic for long intervals

Fixed trader creation in cities

Support for creating trade cities under siege

Risk system now depends on difficulty and house value

Improved tutorial system

Support for multiple temple complexes and monuments (optional)

New tax collection system (optional)

Improved labor system

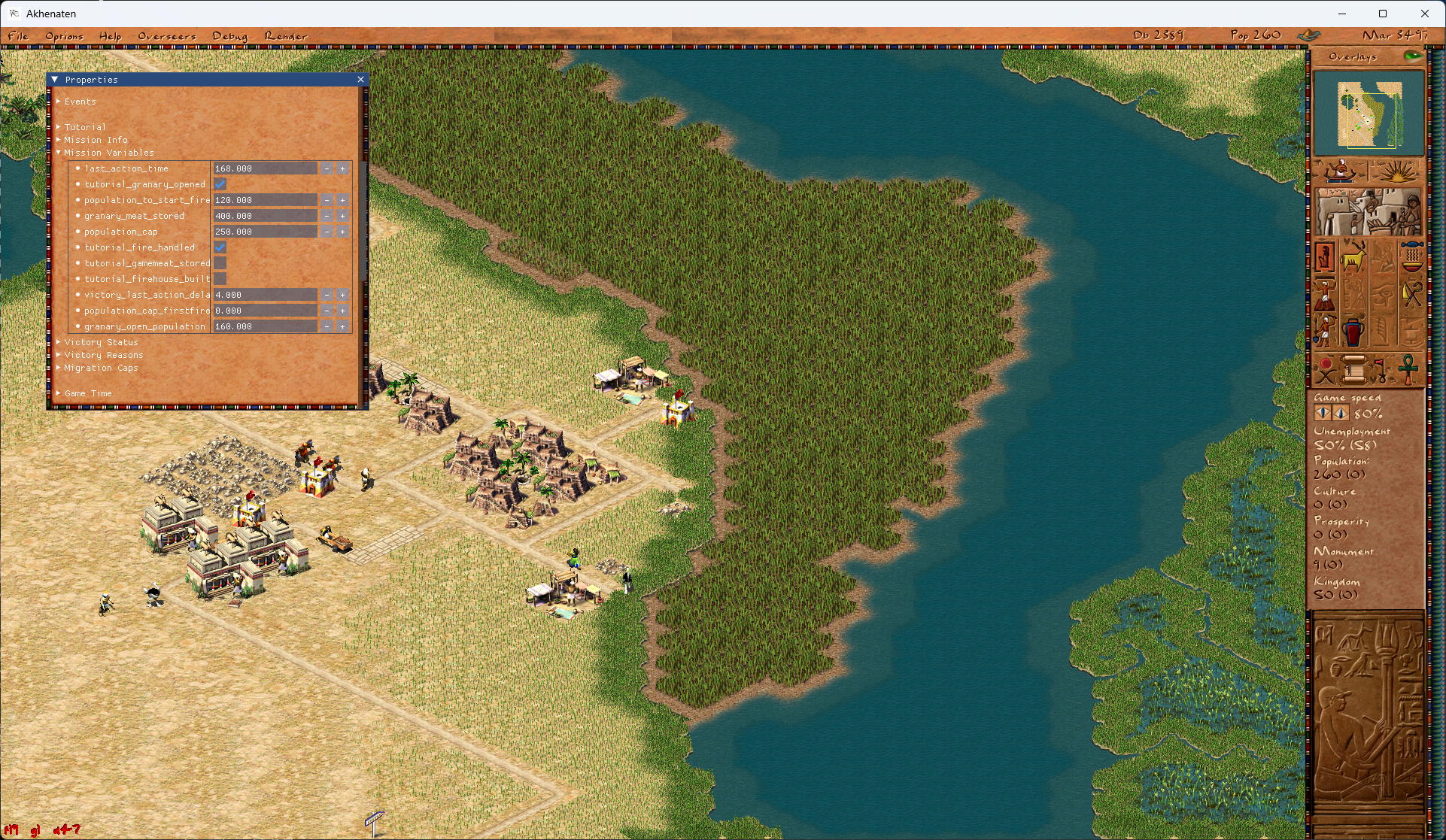

Developer Tools

Sprite tool for viewing game resources

Improved debugging tools

Console commands for creating figures and game management

Font generation tools

Debug modes for routing

Debug rendering for canals, gardens, enemies

Game++. Cooking vectors (part 2)

Hybrid vector

From a memory perspective, hybrid_vector is essentially a static_vector that can allocate space for any number of elements, but if the number of elements is below a certain threshold, it uses its internal storage.

A similar effect is used in the optimization for small strings known as SSO (Short String Optimization) by Alexandrescu. The idea is to use class member variables as an internal buffer, interpreting them as a byte array. A string object typically stores a pointer to the string buffer, but on a 64-bit system, a pointer alone can hold up to 8 characters without allocating memory.

A typical string implementation also stores the size, capacity, and sometimes a checksum along with the buffer pointer. These fields combined can be reused directly as internal storage for the string, as long as the string length stays within a certain limit—typically around 16 characters.

If data is created temporarily on the stack—such as local variables in a function that stores intermediate computation results—then a hybrid_vector can store all its elements locally, without any dynamic memory allocation, similar to C++ static arrays.

For example, suppose we know that NPCs usually carry no more than two types of weapons, but assault units might carry an additional machine gun. In this case, it's more efficient to give all NPCs a hybrid_vector. Most of them will store their data internally within the class, while assault units will get a dynamically allocated memory block. Since assault units only make up, say, 1 in 10 NPCs, we only "waste" some memory on the unused capacity for two weapons in the other 90%, but in return we get fast access to NPC parameters and avoid heap allocations in the vast majority of cases.

: Cases :

Using a hybrid_vector comes with additional design overhead. There are cases where it may bring no benefit at all.

The lack of a reasonable "small" value for N, or bloating the class data, doesn’t come for free either.

If the typical size is much smaller than N—when most use cases require less memory than the internal buffer provides—you also need to watch memory allocations closely. However, it’s much easier to monitor them compared to standard container classes, because you can always attach custom metrics or counters.

Large element sizes can also be a problem. If each element takes up a lot of memory, the benefit of data locality is offset by the increased memory footprint. In that case, the primary motivation behind this class—improving data locality for better cache performance—gets diluted. The performance gain is negligible, and you end up with speeds comparable to using heap-allocated arrays.

But again, everything depends on the algorithm and the hardware. On older mobile devices and consoles, performance gains were noticeable up to about half a kilobyte on the stack. After that, performance would degrade, and somewhere around 16 KB it would become comparable in speed to heap allocation. On modern processors, this difference is much less significant—as long as the stack size is sufficient.

Starting with C++17, the standard library introduced a way to emulate a hybrid_vector using custom allocators:

char buffer[64] = {}; // a small buffer on the stack

std::pmr::monotonic_buffer_resource pool{std::data(buffer), std::size(buffer)};

std::pmr::vector<char> vec{ &pool };

In a certain sense, you can trace a dependency path from vector to array, where performance improves at the cost of reduced flexibility (or increased memory usage). In most cases, the full flexibility of vector isn’t actually needed—it’s often used as a convenient but thoughtless default, simply because it offers access to the full STL toolkit.

However, that convenience comes with responsibility. Nowadays, not all developers even understand how std::vector works under the hood or what specific considerations come with its use.

: Links :

https://pvs-studio.com/en/blog/posts/0989/

https://github.com/palotasb/static_vector

https://github.com/gnzlbg/static_vector

https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/container#Container_adaptors

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/csharp/programming-guide/arrays/multidimensional-arrays

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/csharp/language-reference/builtin-types/arrays#jagged-arrays

https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=kPR8h4-qZdk

https://www.open-std.org/jtc1/sc22/wg21/docs/papers/2023/p0843r6.html

https://www.cppstories.com/2020/06/pmr-hacking.html/

Game++. Cooking vectors (part 1)

In game development, dynamic and static arrays are the primary tools for working with collections of objects—I'll refer to them as vectors from here on. You might think of various map, set, and other optimized data structures, but those are often also built on top of vectors. Why is that? Vectors are simple to understand and convenient for a wide range of tasks, especially when the size of the data is unknown or only approximately known in advance. But, as you might expect, everything comes at a cost—and in this case, the cost is performance, which is, as always, in short supply. So, the use of dynamic arrays comes with its own limitations and trade-offs.

std::vector and its analogs are often used to store everything from game objects like entities to textures, network packets, and tasks in schedulers. Fortunately, it's relatively easy to implement and maintain. It’s a container with a contiguous block of memory that can store an arbitrary number of elements. Each time the capacity increases, the vector allocates a new memory block of the larger size and copies the old elements into it. However, there are pitfalls—especially when dealing with elements that require copy operations. This can become a non-trivial issue, particularly when some classes are non-copyable at all.

Allocations

The C++ standard does not mandate any specific behavior regarding memory allocation for an empty std::vector. When a std::vector is created, it may pre-allocate memory sufficient to hold a certain number of elements. The size of this initial block can vary depending on the compiler and STL implementation. For example, Nintendo’s implementation of std::vector always allocates space for 4 elements upon declaration.

From the compiler's point of view, if such an array is declared, it's likely to be filled—so why not allocate memory up front? In general, this is a reasonable strategy, with one small caveat: it works well mainly on Nintendo’s platform, which has a dedicated allocator for small allocations (up to 128 bytes). If you go beyond that, you're either stuck with the regular, slower allocator or you need to implement your own.

When the number of elements exceeds the current capacity, std::vector increases the size of its allocated memory block. Typically, this capacity is increased by a growth factor (often multiplicative), but the exact factor depends on the implementation. Some use adaptive strategies based on the current size to minimize reallocation costs, while others apply a fixed multiplier.

During a resize, all existing elements must be copied to the new memory block. This can be an expensive operation, especially if the elements have complex constructors or destructors. Since most std::vector implementations rely on dynamic memory, this process contributes to memory fragmentation—particularly on resource-constrained platforms like consoles.

After resizing, a portion of the allocated memory remains unused to reduce the frequency of future reallocations. This is a trade-off between memory efficiency and performance. It becomes particularly noticeable with large vectors and auto-managed capacity growth. For example, even if you have only 100 actual elements, the vector might have memory allocated for 150–200. If vectors are used without careful consideration, this leads to the classic question: “Where did all the memory go, bro?”

Not all vectors are equal

Well, are there enough downsides to the fastest and most popular container in game development? Let's take a look at how we might get rid of some of them. Of course, we can’t eliminate all of them—games have become really hungry for memory, and sometimes even a 2MB thread stack isn't enough anymore. But before diving into tricks and alternatives, let me quote a legendary developer:

Programmers waste enormous amounts of time thinking about, or worrying about, the speed of noncritical parts of their programs, and these attempts at efficiency actually have a strong negative impact when debugging and maintenance are considered. We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%.

You’ve probably heard the short version:

Premature optimization is the root of all evil.

In other words: don’t waste your time without profiling first—you’ll just end up chasing shadows.

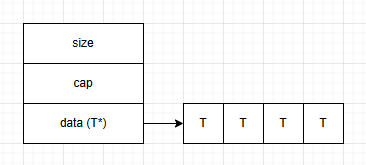

When designing gameplay logic, we often aim for one-shot composition (linear or multidimensional) using arrays to maintain good cache locality, fast access, and efficient processing. Contiguous memory layouts offer a significant performance advantage, making this classic std::vector-style data layout the most efficient among alternatives. It typically looks something like this:

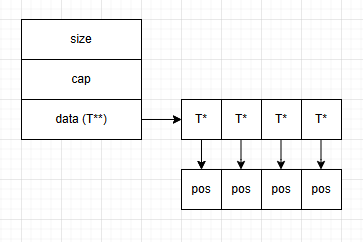

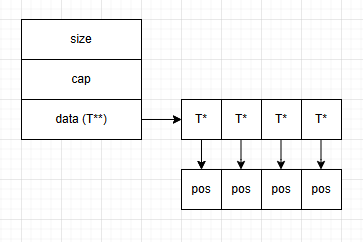

But due to the size and dynamic nature of objects, we often end up with two-level composition. However, in terms of memory layout, a std::vector of std::vector is not an extended version of a multidimensional array in C++. The former stores its elements in a single contiguous block of memory, while the latter does not. Roughly speaking, it looks like this:

A two-level or cascading std::vector structure has a memory layout similar to std::deque, which almost guarantees CPU cache misses unless additional effort is made. Modern processors can more or less efficiently handle double or triple pointer indirection, but performance drops drastically with higher pointer dimensions.

Moreover—and this is more critical—a cascading std::vector structure requires multiple memory allocations, whereas a true multidimensional array needs only one. Unfortunately, achieving single-level composition isn’t always possible without hacks or heavy restructuring, so the second approach is much more common in practice.

When developing software—especially performance-critical systems—memory allocation becomes a serious bottleneck. Last year, Sony introduced a preview requirement that even under heavy scene load, the framerate must not drop below 60 FPS (as lower framerates allegedly hurt user experience). That gives us roughly 16 milliseconds to prepare a frame.

A system call for memory allocation typically takes 1–10 ns, assuming no collision with another allocation. If there is a collision, the time can rise to around 40 ns—or even up to 120 ns if the new operator or malloc() triggers a system call to grow the heap, which involves switching to kernel mode and possibly stalling the thread. There are, of course, specialized allocators for games and real-time systems, such as TLSF or jemalloc.

As you can see, even a single memory allocation can become a bottleneck if it occurs inside frequently executed logic. In game development, dynamic memory allocation is generally prohibited during gameplay—95% of the time, such code will be rejected during review. Unless there's a very compelling reason, you can't just allocate memory wherever you want. Anything that can be allocated should be allocated before the level starts.

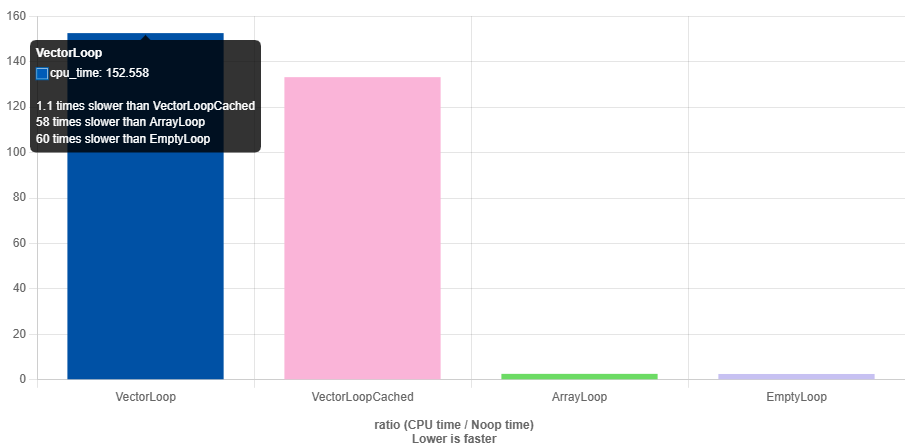

std::array

The first thing to consider when you want speed but don’t want to write your own classes is the standard C++ array. It contains exactly N elements, which are initialized upon creation. Of course, it’s not as convenient as std::vector, which can dynamically grow and doesn’t trigger constructors until needed. With arrays, you also have to manage the size yourself through an extra variable. Additionally, arrays call constructors for all their elements, which can hurt performance. It’s not the most convenient option, but in critical cases where no better alternatives exist, it works fine.

std::array is simply a static C++ array extended with STL capabilities. Its size is always equal to N, and that value is a compile-time constant.

std::vector vec = {} // 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

std::array vec = { 0 };

int vec_size = 0;

https://quick-bench.com/q/ScPhKA9CEtFcZp4DLLgTVBhFVfU

But replacing everything with std::array doesn’t always work either — we once ran into serious problems while porting a game from PS4 to Nintendo Switch. There was a piece of code with roughly 20 if branches, and in each branch, a temporary object was created. The code worked perfectly fine on PS4, but on Switch we needed a 21st if with its own temporary object. The thing is, PS4 allowed for a 2MB stack, and by the time this function was called, around 460KB was already used. On the Switch, however, the stack couldn’t exceed 480KB for any thread, so all it took to blow the stack was allocating about 20 more kilobytes.

Now, 20KB on the stack is laughably small from a game programmer’s perspective. You might say, “Good developers don’t allocate 20KB objects on the stack,” — fair enough. But what about ten 2KB objects? That’s the real root of these large stack usages and 2MB thread stacks. Just look at the example above: replace a std::vector with a std::array, and boom — 128KB disappears into thin air. All for the sake of performance. Sure, it’s not always elegant, but it’s fast — with a bit of music and dance during debugging.

Static vector

The inconveniences of working with std::array have led developers to create and continue using custom vector implementations that can be stack-allocated. If we continue refining the example from the previous paragraph, we arrive at a class that, through some internal structure, can store data locally (within the object itself).

If we know that the size of such a vector will not exceed N, we can use that fact as the foundation to replace a dynamically allocated vector with one that uses static allocation. In game engines, such a class appeared very early on due to the need to optimize frame times. In frameworks like EASTL, Boost, Folly, and others, this kind of container started appearing around 2014–2015, yet it’s still absent from the C++ Standard Library. There have been proposals for such a class, but even the C++26 standard doesn’t include it. static_vector eliminates most memory allocations in functions, but the tradeoff is the requirement for large stacks — often 2MB or more — and even that isn’t always enough.

In the standard library, we can use pmr::vector with a custom allocator that prevents it from allocating more memory than was preallocated at design time (example below). However, this isn’t always convenient. There’s still a fallback to the heap, but the buffer size is typically chosen so that assertions don’t fire. The allocator itself is very simple and assumes the developer knows what they’re doing. It also has one particular quirk — if you find it, drop it in the comments.

// Initial allocations come from a fixed buffer, with later allocations just doing new / delete

// Pass a type and a count that will typically be used in the allocations for sizing the fixed buffer

template <typename T, size_t COUNT, size_t FIXEDSIZE = COUNT * sizeof(T)>

struct FixedMemoryResource : public std::pmr::memory_resource

{

virtual void* do_allocate(size_t bytes, size_t align) override

{

// Check if free memory in fixed buffer - else just call new

void* currBuffer = &mFixedBuffer[FIXEDSIZE - mAvailableFixedSize];

if (std::align(align, bytes, currBuffer, mAvailableFixedSize) == nullptr)

{

assert(false && "allocate more that expected");

return ::operator new(bytes, static_cast<std::align_val_t>(align));

}

mAvailableFixedSize -= bytes;

return currBuffer;

}

virtual void do_deallocate(void* ptr, size_t bytes, size_t align) override

{

if (ptr < &mFixedBuffer[0] || ptr >= &mFixedBuffer[FIXEDSIZE])

{

::operator delete(ptr, bytes, static_cast<std::align_val_t>(align));

}

}

virtual bool do_is_equal(const std::pmr::memory_resource& other) const noexcept override { return this == &other; }

private:

alignas(T) uint8_t mFixedBuffer[FIXEDSIZE]; // Internal fixed-size buffer

std::size_t mAvailableFixedSize = FIXEDSIZE; // Current available size

};

There are plenty of examples of static_vector implementations on GitHub — you’ll have no trouble finding one that suits your needs. For my own project, I use this one:

https://github.com/dalerank/Akhenaten/blob/master/src/core/svector.h — it’s a custom implementation with minimal dependencies (since Boost/EASTL/Folly tend to pull in a lot of headers).

The next step in the evolution of the static vector concept is the hybrid vector

To be continued…

Game++. String interning

"String interning", sometimes called a "string pool", is an optimization where only one copy of a string is stored, regardless of how many times the program references it. Among other string-related optimizations (SWAR, SIMD strings, immutable strings, StrHash, Rope string, and a few others), some of which were described here, it is considered one of the most useful optimizations in game engines. This approach does have a few minor drawbacks, but with proper resource preparation and usage, the memory savings and performance gains easily outweigh them.

You’ve 100% written the same string more than once in a program. For example:э=

pcstr color = "black";

And later in the code:

strcmp(color, "black");

As you can see, the string literal "black" appears multiple times. Does that mean the program contains two copies of the string "black"? And moreover, does it mean two copies of that string are loaded into RAM? The answer to both questions is — it depends on the compiler and vendor. Thanks to certain optimizations in Clang (Sony) and GCC, each string literal is stored only once in the program, and therefore only one copy gets loaded into memory. That’s why, sometimes, certain tricks become possible.

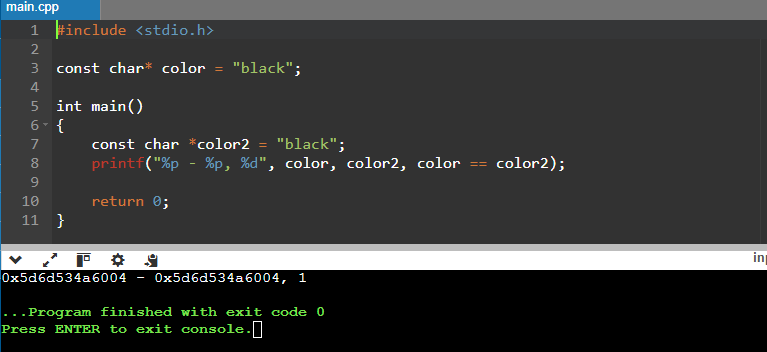

Here sample (https://onlinegdb.com/ahHo6hWn7)

const char* color = "black";

int main()

{

const char *color2 = "black";

printf("%p - %p, %d", color, color2, color == color2);

return 0;

}

>>>>

0x603cc2b7d004 - 0x603cc2b7d004, 1

But on Xbox, this trick won’t work.

00007FF6E0C36320 - 00007FF6E0C36328, 0Is the compiler to blame?

Not really. The standard doesn’t actually say anything about string interning, so this is essentially a compiler extension—it may eliminate duplicates, or it may not, as you’ve seen. And this only works for strings whose values are known at compile time, which means that if your code builds identical strings at runtime, two copies will be created.

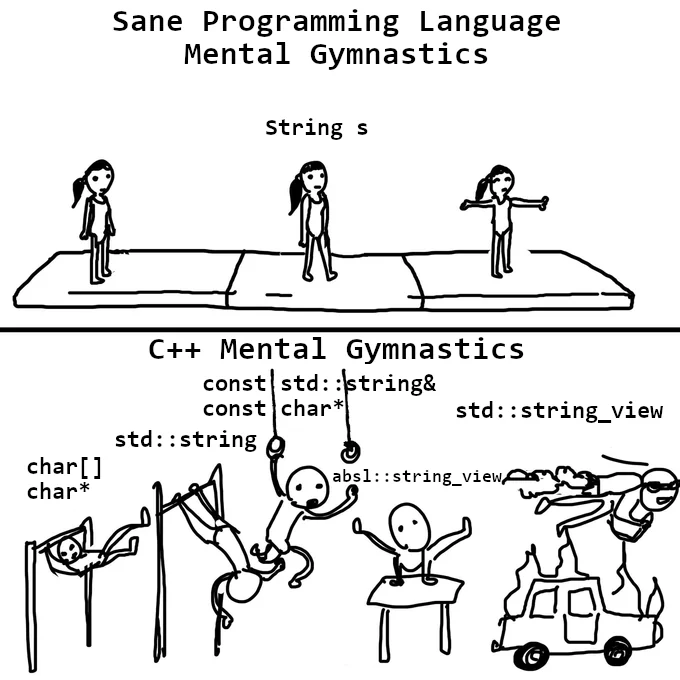

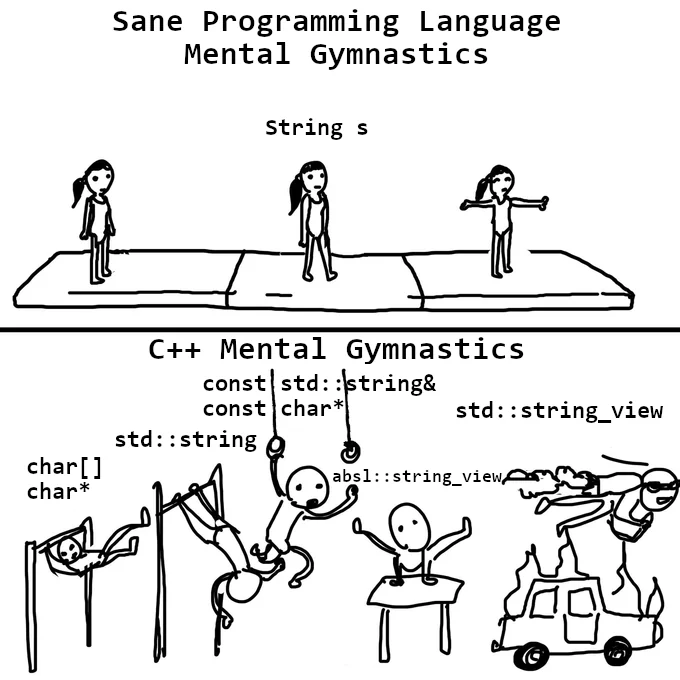

In other languages, like C# or Java, string interning happens at runtime, because the .NET Runtime or Java VM implements this optimization out of the box. In C++, we don’t have a runtime environment that can do this optimization for us, so it only happens at compile time. But what we do have is a game engine and dedicated programmers who can implement it themselves.

Unfortunately, this optimization is very fragile: there are many ways to break it. You’ve seen that it works fine with const char*—and even then, not always:

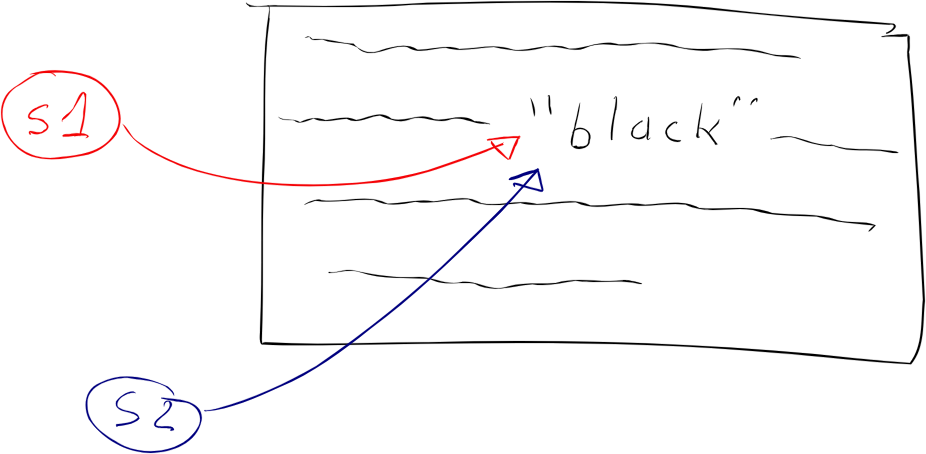

// Number of copies: 1 in rodata, 1 in RAM const char* s1 = "black"; const char* s2 = "black";

But if we change the type to char[], the program will create a copy of the literal when initializing the variables:

// Number of copies: 1 in rodata, 3 in RAM const char s1[] = "black"; const char s2[] = "black";

Likewise, if we change the type to string, the constructor will make a copy of the string:

// Number of copies: 1 in rodata, who knows how many in RAM if you put this in a header const string s1 = "black"; const string s2 = "black";

String Comparison

Now that you've seen some of the quirks of working with such strings on different platforms—and you know how this optimization can be broken—let's look at string comparison using the == operator. Everyone knows that using == on pointer types, including string literals, compares addresses, not content, right?

Two identical string literals can have the same address if the compiler was able to merge them—or different addresses if it wasn’t.

const char* color = "black";

if (color == "black") { // true, string interning

// ...

}

Magic—but it works on the PlayStation.

Everything’s fine… until it’s not—because the moment one of the strings doesn’t get optimized, it all falls apart.

const char color[] = "black";

if (color == "black") { // false

// ...

}

Some might think it’s stating the obvious—but it really can’t be stressed enough: never use the == operator to compare char* strings. And yet, this mistake happens all the time. Just last year alone, I caught six cases (six! In 2024! Four on a Friday, one on Friday the 13th, and two from the same person) where string literals were compared by pointer and caused all kinds of bugs. And about the same number were luckily caught during code reviews.

It seems some people have forgotten that you're supposed to use the strcmp() function, which is part of the standard library and compares characters one by one, returning 0 if the strings match. (It also returns -1 or +1 depending on lexicographical order, but that’s irrelevant here.)

const char color[] = "black";

if (strcmp(color, "black") == 0) { // true

// ...

}

Readability certainly takes a hit—it’s error-prone, and you have to remember how strcmp works—but this is our legacy from plain C, and most people more or less know how to live with it. And of course, performance suffers too, especially on syntactically similar strings.

Not Quite Strings

Ever thought about how memory fragmentation grows when you use lots of string data?

From past experience with regular string and similar types in the Unity engine, total size ended up accounting for 3–6% of a debug build’s memory footprint. Around 3% of that came purely from fragmentation—tiny strings would be deallocated, leaving holes in memory too small to fit anything else. The average size of string data (mostly keys) was between 14–40 bytes, and these little gaps were everywhere. Let’s be honest: 30–60 megabytes of "free memory" on a 1 GB iPhone 5S is more than enough of a reason to optimize it and repurpose that space—say, for textures.

On top of that, these string values aren’t even needed in release builds; they’re only useful for debugging. In fact, the actual string data can be safely stripped from the final builds, leaving only the hashes behind. At the very least, this adds a layer of protection (or at least complexity) for anyone trying to tamper with game resources.

Now add in a linear allocator in a separate memory region, and you can eliminate string-related fragmentation from your build entirely once everything is finalized. Those 6% of test data turn into less than 1% in hashes (just 4 bytes per hash), and we’ll definitely find a good use for the freed-up memory.

xstring color = "black";

xstring color2 = "black"

if (color == color2) { // true

// ..

}

if (color == "black") { // true

// ..

}

On the Tip of Your Fingers

Developers have long come up with different implementations for string interning. When my team integrated this solution into Unity 4, we were inspired by available source code on GitHub and solutions from GCC, but due to open-source licensing constraints, that code couldn’t be directly reused, so we wrote our own. Something similar, I recently came across in the stb library—it was like déjà vu (https://graemephi.github.io/posts/stb_ds-string-interning/).

There are several areas where a lot, a lot, of raw textual data is used, but these strings (which are known in advance) can be hashed: either at runtime or during the content pipeline processing. In the engine, these are prefabs, scene instances, models, and parts of procedural generation. Usually, they are used as independent instances or as templates that can be augmented with other data or components. Other examples include:

Literals hashed in scripts

Tag names in prefabs and scenes

String property values

The idea is quite simple: it’s a basic lookup table that maps identifiers to strings.

namespace utils {

struct xstrings { eastl::hash_map< uint32_t, std::string > _interns; };

namespace strings

{

uint32_t Intern( xtrings &strs, const char *str );

const char* GetString( xstrings &strs, uint32_t id );

bool LoadFromDisk( xstrings &strs, const char *path );

}

}

In the release, during runtime, the engine or game can load a file with hashes and string values if it's required for debugging. In debug builds, strings can be created on the fly directly at the call site. This, of course, is a bit more expensive, but the code remains readable. When we first started integrating this system into Unity, we had a separate object for generating xstring with various masks. This was related to how Unity internally stored string data, and it was more efficient to pre-generate the required identifiers so that they would be stored consecutively, enabling faster processing when needing to iterate through an array of properties. Additionally, in Unity 4, there was a local cache for object components that loaded several subsequent components of an object for more efficient access.

xstring tableId = Engine.SetXString( 'table', 'prop', 0 );

This function led to the creation and hashing of strings like table0prop, table1prop, up to table15prop. It was no longer necessary to separately create table15prop because the engine had already done it. But these are just specifics of how a particular engine was designed, and there's no point in lingering on them, especially since nearly 10 years have passed—maybe they’ve come up with something entirely new by now.

Later, thanks to the simplicity and versatility of this system, I used it with minor variations in other projects and engines. As for the specific implementation, you can take a look at it here (https://github.com/dalerank/Akhenaten/blob/master/src/core/xstring.h). In short, I’ll explain how the code works—it’s actually very simple.

struct xstring_value {

uint32_t crc; // crc

uint16_t reference; // refs

uint16_t length; // size

std::string value; // data

};

class xstring {

xstring_value* _p;

protected:

void _dec() {

if (0 == _p)

return;

_p->reference--;

if (0 == _p->reference)

_p = 0;

}

public:

xstring_value *_dock(pcstr value);

void _set(pcstr rhs) {

xstring_value* v = _dock(rhs);

if (0 != v) {

v->reference++;

}

_dec();

_p = v;

}

...

}

The xstring_value structure stores metadata for a string, and in this specific implementation, std::string was chosen as the storage simply for convenience. In the canonical version, a bump allocator was used, which simply placed a new string at the end of the buffer (it's important to use such xstring structures carefully). This ensured that strings were always alive in memory. The xstring class created a new string (if it didn’t already exist) and stored a pointer to where it was located in memory, or it would retrieve a pointer to an existing copy if the hash matched.

Essentially, these are the main points required for operation—like I said, it's very simple. Below is the code that places a string in the pool. Again, std::map is used for convenience, and honestly, I was too lazy to deal with writing a bump allocator. It only offers a slight performance improvement but a small memory overhead. However, the general approach significantly outperforms standard std::string in terms of creation time when using the system allocator (malloc/new), and in comparison speed as well.

The classic use case for such strings is generating them from scripts and resources, or declaring constant strings in code. If you’ve noticed the xstring class, it has a default comparison operator. Since the class itself is essentially a POD (Plain Old Data) int32_t, all checks boil down to comparing integers. Ten years ago, this provided a performance boost of nearly 30% for animations. Overall, using these strings along with other optimizations made it possible to run Sims Mobile on the iPhone 4S, when the game was originally targeted for the sixth generation and slightly for the fifth. Our overseas colleagues didn’t consider this possible at all.

struct time_tag {

float12 time;

xstring tag;

};

struct events {

static const xstring aim_walk;

static const xstring aim_turn;

};

void ai_unit::on_event(const time_tag &tt) {

if (tt.tag == events().aim_walk) {

ai_start_walk(tt);

} else if (tt.tag == events().aim_turn) {

ai_start_turn(tt);

}

ai_unit_base::on_event(tt);

}

These are some great resources on the topic of string interning. Here's a brief overview of each link:

foonathan/string_id

A C++ library for creating unique identifiers for strings via interning. It maps string literals to unique IDs, which can significantly improve performance when comparing strings or storing many of them.Understanding String Interning

A detailed explanation of string interning, its advantages, and when and how to use it effectively. This article explains how interning works and the trade-offs involved, especially in terms of memory usage and performance.String Interning Blog Post

A blog post discussing the concept of string interning in depth, offering both the theoretical background and practical implications for performance in games and other applications.libstringintern

A C++ library that implements string interning for better memory management. This repository provides a practical implementation of string interning that you can incorporate into your projects.String Interning in C++

An article that focuses on string interning in the context of C++ and Arduino. It explains how string interning can reduce memory usage, improve performance, and is especially useful in embedded systems with limited resources.

Should players be hand-held?

In 1998, at the school where I studied, there was only one computer, which belonged to the principal. Our biology teacher, a wonderful guy who worked as an admin at a computer club across the street at night, was the only person who knew how that box even worked. I used to hang out there occasionally, so at some point, I gained access to the principal's computer, under the guise of cleaning and tuning it up. Every attempt to get me interested in programming ended with firing up SimCity, Caesar, or Settlers and a couple of hours of intense monster battles. Later, after finishing university, I worked in various companies, writing code for projects unrelated to game development, but I constantly dreamed of creating games. I tried working on small games for myself, but in 2006, free engines like Unity and Unreal didn't exist yet. So I mostly ended up writing my own engines from scratch and making various demos, which were promptly forgotten.

I got to start my career in the gaming industry at EA as a game engine programmer, that very Unity, but mostly dealt with low-level optimizations. Quickly, I realized that I liked game design more than programming (I still like both directions, so at some point, I switched to AI). Although programmers weren't trusted with creating levels or game design, during work hours, you could peacefully study how both of them functioned, and you even got paid for it. And not just studying from the outside but also from within. I didn't become a professional game designer, but I still enjoy dissecting how game design is done even now.

I haven't had the chance to work on open worlds, except maybe for Cuisine Royale, which, in a way, isn't quite an honest open world. But tasks like analyzing technical solutions in other games and engines, reading relevant lectures and articles, help understand what decisions designers made during development, and most importantly, why they were made. When immersing myself in a new game, these decisions aren't always so obvious, but after spending close to a hundred hours in Witcher 3 or Zelda, these patterns become visible and easily catch the eye. I want to note that neither of these games makes exploration its main goal. The quests in Witcher tell unique stories, while Zelda, oddly enough, focuses on combat and crafting systems. And what's noticeable is that in these games, it's not necessary to extensively explore the surrounding world. Level design and golden path layout are structured in a way that the games guide the player by the hand, and they still end up near important areas or story quests. And when the opportunity arose to delve into the engine and levels of Metro Exodus, I started dissecting the available materials with interest.

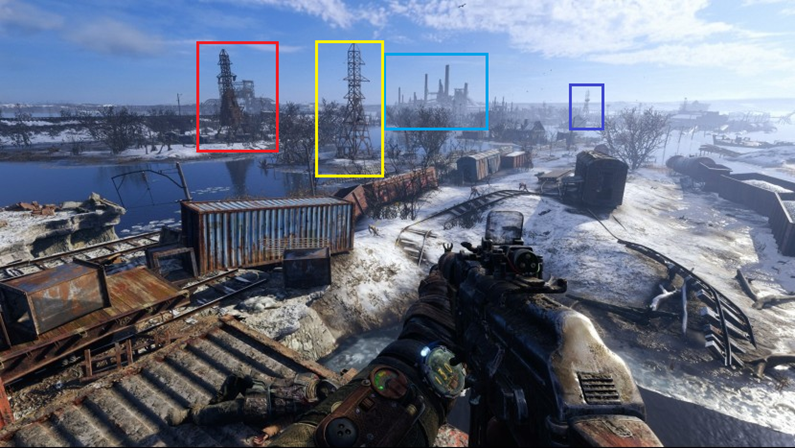

Landmarks

Witcher 3 with its realistic open world, landscapes, forests, and bandit camps, which are mostly uniform and often obscure orientation, along with numerous landmarks, often requires frequent map checking to understand where to go next. Compared to The Witcher, Zelda's levels seem somewhat barren, and it may seem easy to get lost (especially in the desert), but you have to open the map much less often. This is achieved by the placement of objects at the level, special landmarks, and points of interest that can be seen from a distance. Wherever you find yourself, you'll have at least one landmark and a couple of points of interest, and on the way to them, you'll encounter mobs several times, even if they weren't there before (the "five-minute rule"). Have you ever wondered why characters point at something in the distance? Usually, this is accompanied by comments or even a separate cutscene with unique animations, although they will only be seen once throughout the game. This is because landmarks are a great way to orient the player in the world, advance the plot, solidify a final moment, and tie up non-storyline quests or activities.

Do you know what else such landmarks are called? (Weenies) "Weenie" - this term was coined by Walt Disney; he noticed that his dog's head always followed his hand when he held a hot dog. Cinderella Castle in the center of Disneyland is the main "weenie." Two others are Matterhorn Mountain and Big Thunder Mountain. He wanted guests to always know where they were in the park just by looking at the "weenies."

This rule is also used in game from any point in the level, you'll see at least one landmark that catches the eye. It becomes especially interesting to play if you disable the navigation aids in the game. Try it out – both The Witcher and Zelda, as well as Metro, become completely different games when you don't have the option to peek at the map.

Golden path (Story)

I don't like just following the story. The plot, spread out at the level, takes up no more than a third of all content, or even less (these are quite subjective observations, I don't claim to be conducting research here). Maybe that's why I never got past half of Morrowind, even though I started playing it four times, got lost somewhere in the mountains, and suddenly it was already five in the morning. But some people enjoy simply following the yellow point on the compass, map, or whatever else, especially if there are still a dozen games in the backlog that they also want to complete. It heavily depends on the type of player or even their current mood. I prefer immersing completely into the game, exploring different corners, reading level-scattered notes, and finding items, discovering interesting details. The best thing designers can do is create an interesting world that naturally leads you to such places, showing signs of the world to those who have turned off the quest marker or even the entire UI. You know what's funny – such signs usually remain from the very early stages of game development when the designer didn't have final textures and objects yet, and instead, there were placeholders to speed up testing and iterations. Then they become enriched with lore, designers try to integrate them into the game world, and the floating text in the air turns into a sign or a pointer.

In the context of the golden path, returning to landmarks, it's important to note that simply placing a huge tower far away in the level would be uninteresting; its sight would quickly become tiresome. Therefore, designers use an architectural term called "hide and reveal," where the landmark is periodically hidden from view and then revealed again from different angles as you progress through the level. This principle is not new; the Romans used it when building their temples.

Breadcrumbs (Hints)

Above were screenshots of explicit indicators of where the player should move to progress the plot, but this is uninteresting, breaks the game's immersion, and quickly becomes tedious. Therefore, explicit indicators are rarely used or are reserved for special places, like peaceful locations, level entrances and exits, or areas with obvious biome changes. It's much more interesting when designers can work with light and shadow, interactive elements such as crates, diaries, or collectibles. In game "go where it's brighter" principle is used almost everywhere in indoor locations, starting from placing lamps on walls and ending with glowing mushrooms. Even the placement of enemies in the level can be done in a way to guide the player to the next plot element. How many times have glowing mushrooms led you to a checkpoint?

Ideally, of course, the level should be designed in a way that naturally guides the player through the plot, and mushrooms here, as well as yellow stairs, are more like a "crutch" when other visual solutions aren't found. But in the early stages of level construction, such breadcrumbs are used as a support for building more complex plot mechanics. Highlighting certain elements of the game with color is also one of the options for hints.

If we continue the idea of hints, they can be divided into positive and negative ones. For example, you can teach the player that blue doors don't open, and always follow this rule to maintain consistency. However, this also provides opportunities for different puzzles and plot twists when there's no choice other than the blue door, as long as it's justified; otherwise, it would break the atmosphere. Negative hints allow for clear limitations in the level where the player cannot go, such as poisonous areas, burning objects, radiation zones, etc.

Walls

I believe that in most modern games, designers have become a bit lazy and often use invisible walls, but I may be mistaken. This thought came to me when I tried to explore levels not related to the plot, which often led to such limitations that, of course, broke the atmosphere. Yes, I understand that it's a game, but I hope that in modern games, there will be fewer invisible walls. For the sake of fairness, I want to say that old games like Quake or Unreal didn't have such a problem because they were more enclosed, with corridors and rooms that almost always had visible boundaries from all sides, i.e., walls were physical and visible, and this didn't cause irritation. Even the open spaces in Unreal had natural limitations such as cliffs or mountains where I physically couldn't go. But when I can't pass through a partially destroyed door, even though I broke down a wall before and opened exactly the same door as part of the plot, it's certainly irritating. And this is despite the fact that many modern games are open-world exploration, but designers have been lazy to incorporate limitations into the gameplay. In this place, I can't jump on the boxes, although I easily did it a bit to the side.

The key here is to incorporate, to clearly explain why the player cannot go somewhere. Placing a car, a ravine, a toxic puddle, or even a fence made of barbed wire in the way would work! Anything that fits the game world. A fence made of barbed wire or an iron-barred door is perfect if you need to show the place where the player should go through. At least through it, everything is visible.

Another way to restrict players from exploring certain areas is by using gates that open after solving a puzzle. Shooters have become adept at incorporating simple puzzles, like reaching point B, killing everyone along the way, pressing a button there, then returning and defeating everyone behind the door.

Affordance

Natural level constraints such as walls and cliffs create excellent enclosed spaces that can be broken down into areas of accessibility using doors, stairs, crawl spaces, and places that significantly change the player's vertical position. Enclosed spaces are great because they allow you to tell and show the player a memorable little story, introduce new characters, give them the opportunity to save, and better remember the impressions of the last minutes of the game. At the same time, designers consider the appearance of these elements, making and placing them in the level so that their appearance corresponds to their function. If it's a ladder, you should be able to climb it; if it's a hole, you should be able to crawl through it; if it's a door, you should be able to unlock it; if it's a cabinet, you should be able to open it, and so on. Therefore, when one door opens while the one next to it does not, it causes irritation and confusion. Affordance (Accessibility) is one of the most commonly used methods of storytelling and perhaps the simplest.

Visual shapes

Expanding on the idea of accessibility, one can consider that not only active objects have clearly distinguishable features, but the shape itself can serve as a signifier. For example, for shelters (rectangular objects at waist level), which the player will learn to recognize. After crouching behind such objects several times and realizing that this shape provides safety during combat, the player will continue to apply this knowledge throughout the game. This is related to the characteristics of human perception of shapes; round objects are perceived as soft and fragile, while square ones are perceived as solid and reliable. Triangular-shaped objects are perceived as dangerous.

In addition to shape, as with hints, color can also be used. Then the purpose of items will be determined without hints, as is done, for example, for electrical boxes (yellow) and canisters (red). Generally, the use of contrasting colors to draw attention to where to go is widely used in games. Here bright yellow boxes, interactable ladders, and objects of red color if they need some part for activation are used. This subtly hints to the player what is expected of them to solve the puzzle. And most people won't question what to do once they've already solved a similar puzzle before.

By the way, if you didn't notice, the color of the dynamo's lighting is also yellow. The game uses various combinations of contrasting colors, flashing lights, glowing mushrooms, moving water, additional lighting of objects, etc. All of this attracts the player's attention to the required direction.

Device lock

Another natural limitation is device locks or special items. Players are free to explore the world but cannot progress through the story or enter another location until they acquire the necessary item. Designers widely apply this pattern to restrict access to locations at specific times. Moreover, if the item uses consumables, it significantly expands the player's time management options. This also enhances non-linearity, as we all love non-linear games, or presents the game as non-linear. If the designer adds the ability to explore locations without the necessary item, albeit with limitations, they deserve top marks. In Metro Exodus, the device lock on the Caspian Sea becomes the van. While players can bypass the entire level on foot, story conversations and progressions occur through the "car". In the Valley level, it's the crossbow that serves as the device lock. While you can certainly try to progress without it, the designers have left that possibility open. However, you won't be able to solve some of the puzzles without it.

Another type of device lock is crafting locations where you can obtain new items and abilities. It's not entirely fair to the players because it disrupts the pace of the game, but it allows for dividing levels into locations and logical zones. Usually, entering such places suspends the global time in the game, triggers NPC respawns, switches story states, and quests.

Opennings attracts

Openings like caves, doors, basements, and the like seem to attract people to explore them. While we're not cats, we still love to explore our surroundings just as much. Such spaces also possess an aura of mystery, and people want to find out what lies inside. This attraction also occurs in the real world; for example, urban explorers are fascinated by exploring underground tunnels. Part of this is also due to the fact that open spaces often host combat encounters, while rooms are designated as safe zones, psychologically perceived as secure. Doors and arches also attract attention, even if there's no roof behind them. The folks at Ubisoft shared an interesting experiment at GDC regarding Far Cry 3. They randomly placed arches and door frames throughout a level. A group of testers, who weren't informed about these elements, passed under the arches and door frames twice as often as those who were told they were just test objects. This demonstrates how knowledge of psychology can assist in creating engaging level designs. Skillful application of this knowledge allows designers to draw players' attention to points of interest by shaping the geometry of buildings or objects appropriately.

Another important aspect when creating points of interest is highlighting the transition between spaces, such as moving from outdoor to indoor areas. Typically, different colors are used for interior and exterior walls. The exterior color tends to be cooler, while warm yellow tones are often used indoors. This helps the player understand that the game environment has changed. If both indoor and outdoor areas share the same color scheme, this distinction is lost. For example, in the image below, although the building appears to be constructed from bricks of the same color, they appear warmer inside and cooler outside

Gates & Valves

Gates, doors, and various types of puzzles designed for their opening are one of the cheapest ways to pause the plot until certain conditions are met: kill all enemies, move debris from the road, turn on electricity, etc. It also allows the designer to close the door behind the player, preventing them from returning and unloading the room, tunnel, station, or even half of the level, without worrying about how NPCs will behave in the completed location. Entering this door unloads the entire remaining level, allowing for the use of twice as many NPCs in combat inside and a highly detailed model of a locomotive. And even though they don't show it to you, you still understand that a certain milestone in the plot has been reached, and you need to keep less in mind and focus more on the current task. At first, this may seem useful only for linear games, but open-world games also actively use this approach, for example, unloading the entire or most of the rest of the level while you are passing through a cave or another enclosed space. This approach is well illustrated when Artyom goes to rescue Anna from the bunker; you can't exit to the open world until the location with the bunker is completed, and the rest of the level is maximally unloaded at this moment, allowing for more detailed objects and environment to be placed inside the bunker.

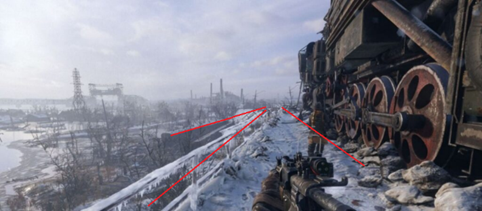

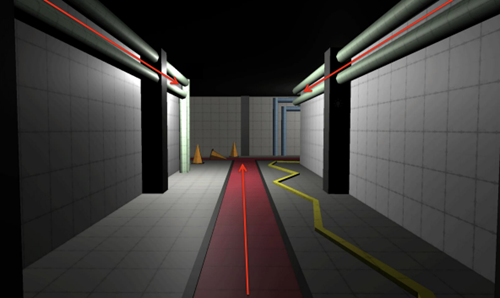

Leading Lines

These lines originated from painting - it's a composition technique where lines on the canvas draw the viewer's attention to a specific point. Similarly, designers use environmental elements to create arrows that look natural but attract attention and indicate the direction for further progression. In games, these are often roads, pipes, cables, and many other objects that players perceive as natural but are deliberately positioned and tuned this way. It may seem distorted due to perspective, but both the wagons on the left and the train on the right are intentionally slightly turned towards the path to form an arrow. This is the first thing a player sees when descending from the Aurora.

Any environmental elements can be combined to serve as clues, even pipes and cables. Notice that the bulges on the pipes are only on the side of the correct exit. You may not explicitly mark this, but our brains notice such placement patterns, and if they are used in the right places, you won't even notice how you're going in the direction the designer intended. However, if they are placed randomly, there will be no effect, just like training a neural network on poisoned data sets; you only get results when the training set is properly composed

For beginning level designers are usually shown this picture, which explains the principle of Leading Lines in simple terms. By extending these lines in the desired direction, you can attract the player's attention to the right and increase the likelihood that they will go there. The pipes on the walls and the central line set the main direction of view along the corridor, but the pipes on the left end, while the pipes on the right turn the corner, directing the gaze. Additionally, the contrasting line (in our case, the yellow wire) draws attention to the turn.

Pinching

The essence of this method is to direct the player to a specific location in the level using environmental cues. This is usually achieved by restricting free movement through strategically placed objects, forcing the player to move in only one direction. People don't like being forcibly led through the story, so obvious pinching is applied with caution, otherwise, it quickly becomes tiresome. Designers always try to come up with natural and explainable limitations, such as with the boat here; there's no other way to reach the monastery except by boat, but this transition is presented very subtly.

On the other hand, the entire Yamantau level is presented as one large corridor-like structure, where the player is given only a few minutes to move left or right. However, this is presented very skillfully from a narrative perspective, and the sensation of an open world from the previous level has not been forgotten, so this diversity works to the game's advantage. According to my colleagues, Yamantau was cut by a third to prevent the corridor-like nature from becoming tiresome.

Framing & Composition

Another technique borrowed from photography into games is framing around an object (landmark, major enemy, important character, cave entrance, etc.), which directs the player's attention to that object. This technique works particularly well when guiding players to beautiful views, transitioning the level's narrative, or introducing important characters. After the game leads the player to a specific location, the frame around the central object adds significance to it. This is best demonstrated in scenes involving Anna - in most cutscenes featuring her, the composition's focus is shifted specifically to her

Here are a couple of book recommendations for your leisure time. I hope you find them useful.

"Level Up! The Guide to Great Video Game Design" by Scott Rogers

"101 Things I Learned in Architecture School" by Matthew Frederick

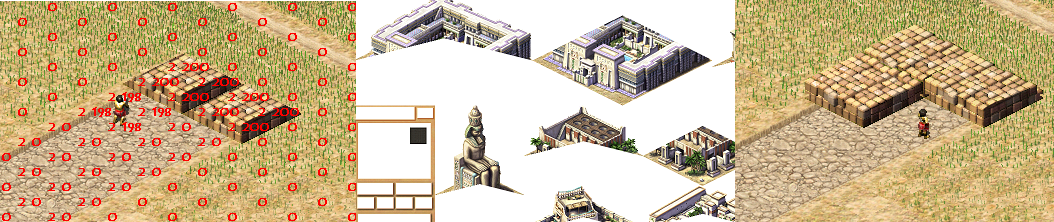

Sprite tool added

Sprite tool allow to view how animation work in runtime, just select item from list

Base class for Hyena animal

Added a base class for Hyenas to the game. It's not very functional yet, but it's another step toward restoring the game.

Code placed here figure_hyena.h

The Story of original Pharaoh game

It all begins with an idea.

I am a longtime fan of Impressions Games(c) city builders and Simon Bradbury, in case you don't know - his genius gave life to games like Caesar 1/2/3(c), Space Colony(c), and the entire Stronghold(c)(c) series, where he still works at Firefly Studios to this day. Caesar became a hit project and sold over 400k copies on disks over two years from 1998 to 2000. But the best game of the series is considered to be Pharaoh + Cleopatra (c).

The development of Pharaoh began in the fall of 1997, roughly a year before Caesar was released, but even after two years of active development, only part of the planned mechanics were implemented. Some of them were later added in the Cleopatra addon, while others, like dynamic trading with cities, labor markets, weather, and dynamic map changes, were only realized in the next series games . Even the setting itself was not fully defined, and some animations were still in draft form, while others were borrowed and redrawn from Caesar.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

Be clear, be confident and don’t overthink it. The beauty of your story is that it’s going to continue to evolve and your site can evolve with it. Your goal should be to make it feel right for right now. Later will take care of itself. It always does.

After the release of Caesar 3, the founder of the company, David Lester, left the team, and control was taken over by lead designer Chris Beatrice. As one of the company's veterans, he had helped create many systems that allowed it to function and grow. "Remember, I'm an artist," Chris told his colleagues, "I was never a game designer or a CEO." In 1998, the roman city-builder Caesar 3 was at the peak of its popularity, but instead of revisiting Ancient Rome with deeper mechanics and the begining trend for 3D games, Chris and his team decided to change the setting to something more ambitious.

There was still a year to go before the expected release next game, but due to disagreements and Simon's dissatisfaction with the management and the intense pressure to meet deadlines, he left the studio and founded his own (Firefly Studios), where he continues to create games to this day.

S.B. -"Chris was always pushing the damn team, trying to come up with some bloody new stuff, and the idea of just sticking with a successful game was like nons heresy - no one did it that way, and it didn't dirty well help the work either."

But let's get back to the Pharaohs, or rather, one Pharaoh.

The studio still had the Caesar 3 engine, which allowed players not only to design their cities but also forced them to deal with an increasingly complex set of demands to maintain prosperity, happiness, and growth. While one of the alternative concepts for city-building games, "Caesar in space," was quickly rejected, the idea of creating a game set in Ancient Egypt/Greece/India sparked tremendous interest from the European marketing team. Before 1999, only three people were working on the Caesar/Pharaoh engine: Simon Bradbury (Render/Code), Gabe Farris (GD/Code), and Mike Jigenrich (Code). About a year before the release of Pharaoh, a team of around 10 people was already working on the Pharaoh game code.

Simon's fires had a very negative impact on the game's progress; some mechanics had to be postponed for the expansion pack. In fact, he was responsible for most of the programming work on the engine and was the main source of knowledge about game, engine and inside mechanics. Simon's name was not mentioned in the game credits, they probably just forgot.

S.B. - "Blimey, they 'ad to bring in five more folks just to do me bleedin' job. Never thought I was worth all this bother."

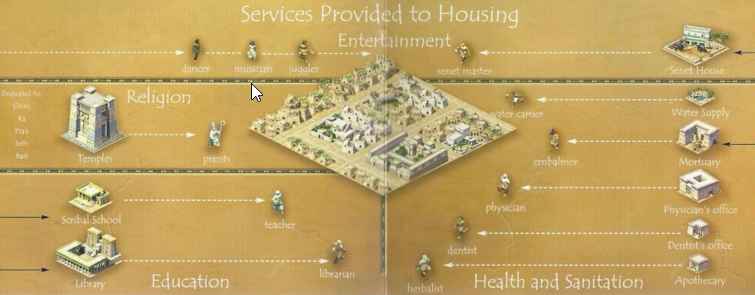

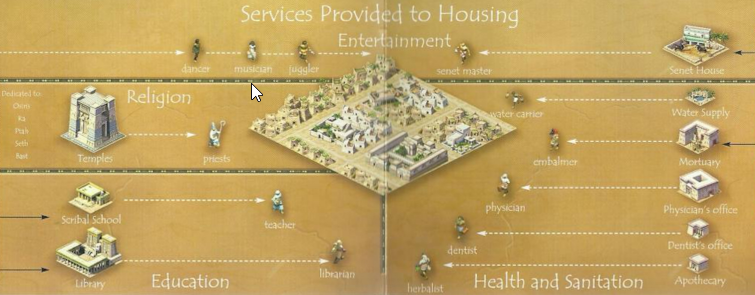

As an example of how complex the social system was implemented in the game, Chris recalls a chain of events related to the educational system:

C.B. - "So, there's this man go to collecting reeds, then those reeds get turned into papyrus. The teacher comes along and takes the papyrus, then the school hires the teacher, who starts educating the kids. Now, the houses need to be of a welthy for the kids to go to school."

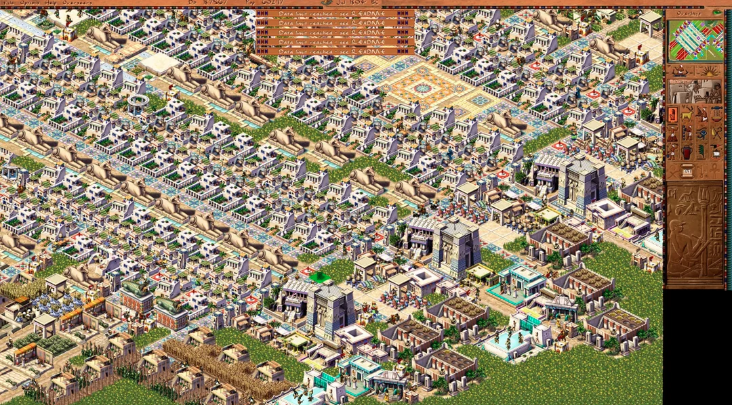

In the way from previous games, in Pharaoh, the npcs actually move between destinations instead of aimlessly wandering around before. When the population reaches thousands, things get incredibly complex, so in order to maintain a steady fps rate, the number of active objects per frame was reduced from 5000 in Caesar to 2000 in Pharaoh. According to Simon's words, even in Caesar, there were significant challenges with implementing the core logic within the limited resources of the processor and memory - the game had to run on just 32MB RAM.

S.B. - "One of the big challenges with city-building games is that there are so many characters moving around that you can't spend too many cycles or memory on each individual character, but the map is constantly changing. Floodplains are not the only things that change. The player can build a new road, destroy a road section after a destination has been calculated, or leave a wandering character stranded without a way back. So, we used simplified simulation for objects on the same tile. One NPC would perform the main action, and copies of the instructions were given to the others."

Haidi Mann was lead of the game's graphics, and she had previously worked on Caesar 2/3. As the lead artist on the project, she was responsible for creating the overall visual style of the game. Despite the game being set on a 2D grid, "Pharaoh" had amazind 3D graphics. The game's objects were first assembled in a 3D package, then a grid of tiles was placed over them, and artists manually redraw and applied to the original textures, giving the whole game a high-quality and picturesque appearance. Later, Haidi would refer to this technique as "ping-pong texturing" in one of her interviews. Technically, Haidi was the lead artist, but roles within the team were relatively - she worked on animations, while Chris, for example, handled everything for the ostriches, from code to textures.

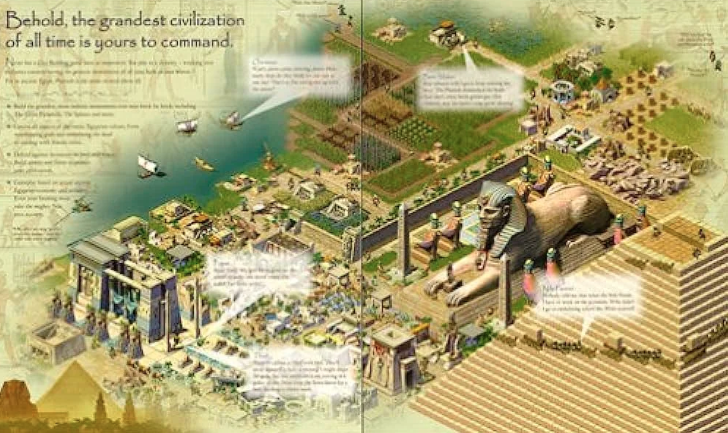

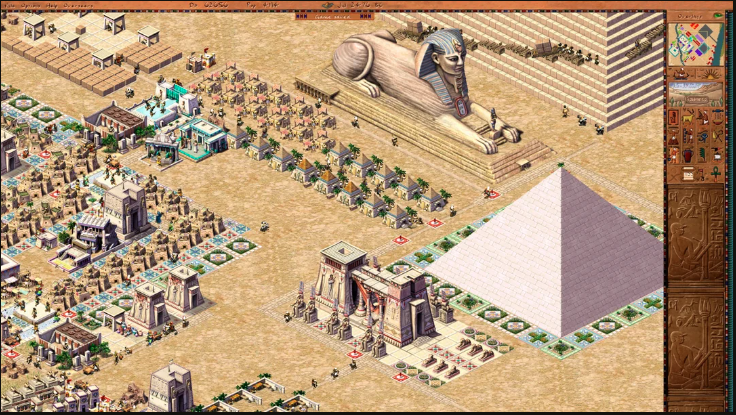

According to the game's fans, the addition of monuments in Pharaoh transformed the game into the best city-building game of its time. Unlike Caesar and other city-building games before it, it was challenging to give players a main goal. There were general goals like "more population," "happy citizens," "full warehouses," and others, but they still didn't provide a humankind objective. However, when your city is functioning strong, and you have the resources to build a massive, truly enormous monument that takes up half the screen (1024×768) and grows before your eyes - for a 2D game of that era, having something so huge on the screen was truly astonishing.

Like in ancient Egypt, these epic structures become the focal point of the society. To build a pyramid from bricks, for instance, players must not only accumulate a vast amount of materials and labor but also establish guilds of carpenters, stonemasons, and bricklayers to form a skilled workforce. It's a complex and challenging task that requires careful planning and management. The game captures the essence of the monumental efforts and resources needed to construct such grand structures in the ancient world.

The ancient Egyptian atmosphere brings a whole lot of interesting new features to the game. Regular flooding of the Nile river demands that the city produces or imports enough food to endure the flood season. A poor flooding can lead to lousy irrigation and food shortages, making the satisfaction of the god of flooding, Osiris, a vital task. The religion system in "Pharaoh" hasn't seen much improvement compared to "Caesar III," but appeasing the gods is now a less prioritized task. There are fewer gods in each scenario, making the process less knotty. These changes enrich the gameplay experience, allowing players to focus on other crucial aspects of developing their city and empire.

Greg Sheppard - the producer of Pharaoh - recalled how the team worked tirelessly to fine-tune the construction mechanics until the very last moment. We were just about to hit the deadline, and the pressure was intense. The game was going to be much bigger than Caesar III, so we needed a robust engine to handle the load. Building the pyramids block by block was a technical marvel on its own. We were still fixing critical bugs in that area just days before the game went gold. It was a nerve-wracking experience, but seeing it all come together was truly rewarding. We put our hearts and souls into Pharaoh, and I'm immensely proud of what we achieved.

While next games from the company only added new gameplay elements without fundamentally changing the core of the game, Pharaoh took a different approach by polishing the visual design and core components based on Caesar's engine. For me, Pharaoh remains the most playable and visually stunning game in the series, perhaps because it has a touch of mystique, a lot of manual arts, and parts the developers' souls – call it what you wish. Just take a look at Heidi's cover art; it captures the essence of the game beautifully. Pharaoh truly stands out as a labor of love and a testament to the dedication of its creators.

The game sales exceeded 1.7 million copies, each priced at $45, while five years since its released in 1999. This remarkable achievement is even more impressive considering the budget for the game was less than $2M. Pharaoh's success accounted for over a third of all sales in the series, making it a significant commercial hit.

After a series of ownership changes, the rights to the game development, settings, mechanics, and engine of the Caesar and Pharaoh series ended up with Activision, though not the rights to the games themselves. The rights to the games (Caesar/Pharaoh) remained with Tilted Mill Entertainment, led by Chris Beatrice. However, in 2013, the studio filed for bankruptcy and closed down, and Chris shifted his focus to developing mobile games.

In 2018, the rights to the music and assets of Caesar and Pharaoh were acquired by Dotemu from the New Zealand-based company CerebralFix. The current ownership status of these rights remains unknown. This year, Dotemu and Triskell Interactive released a remake of the game called "Pharaoh: A New Era."

Two years ago, I stumbled upon the Ozymandias project, which aims to recreate the Pharaoh engine, just like it was done for Caesar. During that time, I mostly assisted the project with advice, sometimes with code, and occasionally delved into complex mechanics. However, recently, the original author abandoned it, and I've decided to continue the development on my own.

Welcome, together much interesting revive ancient pyramids!

PS All trademarks metioned in article are the property of their respective owners

How to build a mastaba

It all begins with an idea.

The game "Pharaoh," released back in 1999, was one of the first games to offer step-by-step building of structures, which also required various resources. Off the top of my head, I can recall the Settlers series, Majesty, and perhaps a couple more. After "Caesar III," where the primary resource for building was coins, this was truly astonishing and innovative. It was a particular pleasure to watch the city come to life during the construction of monuments. I remember just building the minimum necessary infrastructure for a monument and simply observing as architects complained about the lack of materials, slaves ran back and forth between farms and construction sites, and traders periodically sold bricks. The rest of the city, of course, lived its own life. You could even forget about certain parts of the city for a while, and the game would continue. This is when you realize why the game remains one of the best city-building games: the distinguishing feature of the series is its "balance," a balance perfected down to the smallest detail.

Revisiting this part of the game, I can't stop marveling at how it was all implemented on those hardware resources, which were, I must note, very limited. Not everyone had 64MB of RAM back then. One of the innovations of the monuments was that they were composite buildings; individual parts could be replaced with others, which essentially allowed for creating buildings with different appearances from the same set of textures. Nowadays, it seems like this approach is present in every game, but in '99, only a few games could boast such a mechanic.

At first, I tried to reconstruct the original drawing algorithm but quickly realized that not only could I not handle so many 'if' statements, but the compiler couldn't either. So, I had to improvise.

In the original game, players gain access to the first monument in the fifth mission of the story campaign, when the map of Egypt and traders become available. The construction of a mastaba is closely tied to teaching the basic rules of trading. Compared to the previous installment of the series, city modeling didn't change significantly. The primary condition for the development of houses remains the same: it depends on the attractiveness of the surrounding land and the availability of goods from the nearest market. If you have residents, you can develop production, build new resource-gathering buildings, and so on.

The number of people in houses depends on the current level of the house, and each level requires a new type of "resource" for maintenance. Moreover, these resources don't necessarily have to be products or goods; accessibility to temples and services like pharmacies is also required to maintain the house's level. While a single market can suffice for the initial levels of houses covering several dozen homes, it becomes noticeable after the mid-game that the number of buildings a market can support is carefully balanced. Even though reviews never explicitly mentioned it, players figured out that one market can support a maximum of 4 mansions at the highest level. Interestingly, even if their working areas overlap, having two markets doesn't support more than that number.

The hierarchy of needs itself remained unchanged from the previous game in the series. It fit so well with the entire setting of the series that it remained unchanged up to "Emperor: Rise of the Kingdom."

How the built in 1999

The first monument available to the player is the mastaba. In the original, it looks like this at the beginning of construction (screenshot from the original game)

And like this upon completion (screenshot from the original game)

I had to tinker with the algorithm for building the mastaba. At first, I tried to restore the original one, but in the end, I gave up and made it simpler. The original algorithm draws the entire mastaba in one pass on the screen, caching identical images and redrawing residents and buildings that are overlapped by the monument during rendering. It turns out to be unnecessarily complex (don't ask how I managed to restore it from the binary, I definitely gained a couple of gray hairs), below is the code for rendering the mastaba itself.

But then I looked at the resulting code and realized that a month would pass, and all of this would be forgotten because it's too complex. So I started digging through the internet in search of something simpler to understand. The solution came together after reading this article, which describes quite well the principles of rendering composite buildings in isometric view. This eventually led to breaking down the mastaba into its component parts and drawing them based on the general rules of isometric perspective.

On one hand, this greatly simplified the rendering logic and completely eliminated the need for overdraw of overlapping parts because each part is considered an independent building and is drawn based on general rules. On the other hand, now the mastaba consists of three types of buildings: slanted wall, entrance, and solid wall. The peculiarity of this implementation is the necessity to recalculate the rotation for each type depending on the map's rotation and the rotation of the mastaba itself.

Gathering bricks

The textures for the mastaba parts are divided into segments of the same size, from which the entire building is assembled. The size of the mastaba can vary from 2x3 to any reasonable size for a specific map, with the one in the pictures above being 2x5. In the resources, this data is split into two files, mastaba.sg3 — this is the description (sg3 stands for Sierra Graphics V3). The texture compression format, developed by Sierra Entertainment employees in 1988 and used in most studio games, but not well-known outside the studio. It provides good results when packing textures with RGB data in 16-bit, all pixels with a value of 0xf81f are interpreted as transparent, this is done with the expectation of subsequent RLE packing, which can compress such sequences of identical pixels into a couple of bytes. You can read more about the format here.

The texture data is stored in .555 files. Most images are located in the .555 file with the same name as the .sg3 file. This was done with the idea of possible patches, to have the ability to provide users with partial changes. The internet was not particularly fast back then, so saving even 0.5Mb, which the sg3 file occupies, was a significant argument for such an architecture.

The graphic data can be packed in various ways in the .555 files, depending on the type of texture:

Uncompressed — such images are stored "as is" by rows, from top to bottom, left to right in each row. Thus, if the image has dimensions of 20x30 pixels, it means that the data for this image consists of 20 * 30 = 600 unsigned 16-bit integers representing the colors of each pixel.

Compressed — transparent pixels for these images are encoded using run-length encoding. This format has remained since Caesar II and was used less and less over time. The data is processed byte by byte as follows:

Isometric — textures with a width divisible by 30 pixels and consist of two parts:

"Base" part: rhomboid base of the tile, stored in uncompressed form because there should be no transparent pixels. The dimensions of the base texture are determined by the game to which the SG file belongs: Caesar 3, Pharaoh, Zeus use tiles of size 58x30

"Upper" part: the remaining pixels that are not part of the base, and since they can contain transparent areas, they are stored in compressed form.

But that's not all, if you look at an isometric tile, you will notice that half of the space is not used, these are transparent pixels and they can be excluded from the encoding by simply skipping these areas. Thus, only significant pixels are recorded, and the texture size becomes even smaller. For example, with such a packing algorithm, a texture of size 10x6 out of 60 pixels is packed into 36.

Based on this data, which is read, unpacked, and correctly assembled, full-fledged textures are obtained. The storage format was primarily designed for the Windows operating system family and its graphics stack, allowing for quick blitting (overlaying) of textures without transparent pixels.

Preparing the construction site.

The construction process is divided into 8 parts: two site levelings and 6 stages of laying stones. To build a mastaba, stone is needed, and for laying one segment, 400 stones are required, which must be delivered from the warehouse to the construction site. After that, the bricklayers begin laying the stones (screenshot from the open-source version).

The calculation of the required texture turned out to be quite simple; edge textures are used along the edges of the site, while the internal tiles are filled with seamless stone tiles.

For animating the monument construction process in the game, separate types of buildings and inhabitants with corresponding sets of animations were added, which was quite bold for games of that time and resource-intensive. The number of animations doubled compared to the previous game in the series, and the texture volume increased accordingly

Fixing rendering bugs

Due to the new approach to rendering the mastaba, incorrect rendering of individual parts occurred. I had to add a bit more to the renderer to teach the engine to render the top parts of textures. For this, the original texture is divided into two parts: the base and the upper part. Then, when overlaid on top of each other, they will form a cohesive texture, free from rendering order errors in isometric view. All bases can be rendered in the first pass, eliminating overlap with the figures of inhabitants, and then overlay the upper part to hide the inhabitants who ended up behind the building. As a result, we get a normal view of the buildings. (screenshot from the open-source version)

A little bit of magic with C++, wait for a few in-game years, and the construction is completed. Almost.... I still need to tweak the texture indices a bit when changing the city's orientation.

Code and logic reuse.