Game++. String interning

"String interning", sometimes called a "string pool", is an optimization where only one copy of a string is stored, regardless of how many times the program references it. Among other string-related optimizations (SWAR, SIMD strings, immutable strings, StrHash, Rope string, and a few others), some of which were described here, it is considered one of the most useful optimizations in game engines. This approach does have a few minor drawbacks, but with proper resource preparation and usage, the memory savings and performance gains easily outweigh them.

You’ve 100% written the same string more than once in a program. For example:э=

pcstr color = "black";

And later in the code:

strcmp(color, "black");

As you can see, the string literal "black" appears multiple times. Does that mean the program contains two copies of the string "black"? And moreover, does it mean two copies of that string are loaded into RAM? The answer to both questions is — it depends on the compiler and vendor. Thanks to certain optimizations in Clang (Sony) and GCC, each string literal is stored only once in the program, and therefore only one copy gets loaded into memory. That’s why, sometimes, certain tricks become possible.

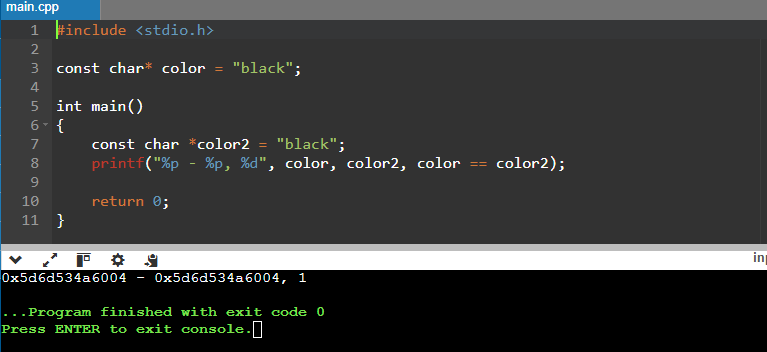

Here sample (https://onlinegdb.com/ahHo6hWn7)

const char* color = "black";

int main()

{

const char *color2 = "black";

printf("%p - %p, %d", color, color2, color == color2);

return 0;

}

>>>>

0x603cc2b7d004 - 0x603cc2b7d004, 1

But on Xbox, this trick won’t work.

00007FF6E0C36320 - 00007FF6E0C36328, 0Is the compiler to blame?

Not really. The standard doesn’t actually say anything about string interning, so this is essentially a compiler extension—it may eliminate duplicates, or it may not, as you’ve seen. And this only works for strings whose values are known at compile time, which means that if your code builds identical strings at runtime, two copies will be created.

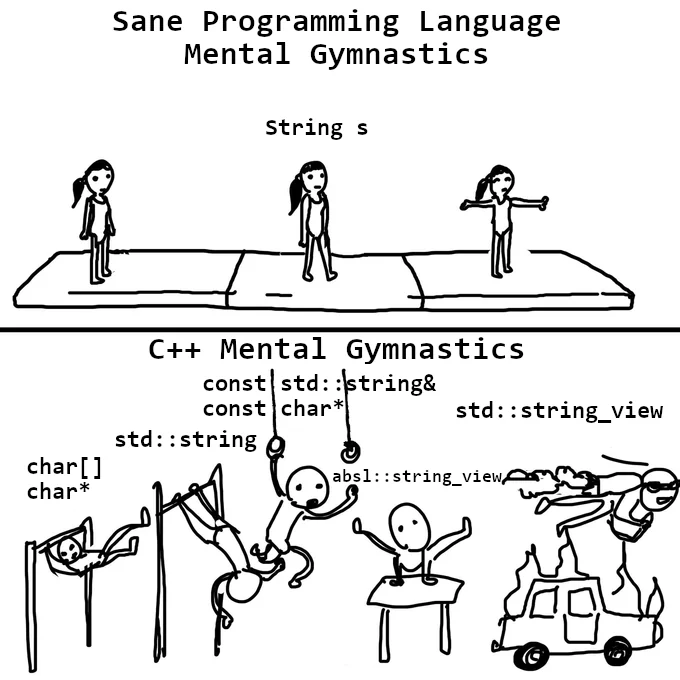

In other languages, like C# or Java, string interning happens at runtime, because the .NET Runtime or Java VM implements this optimization out of the box. In C++, we don’t have a runtime environment that can do this optimization for us, so it only happens at compile time. But what we do have is a game engine and dedicated programmers who can implement it themselves.

Unfortunately, this optimization is very fragile: there are many ways to break it. You’ve seen that it works fine with const char*—and even then, not always:

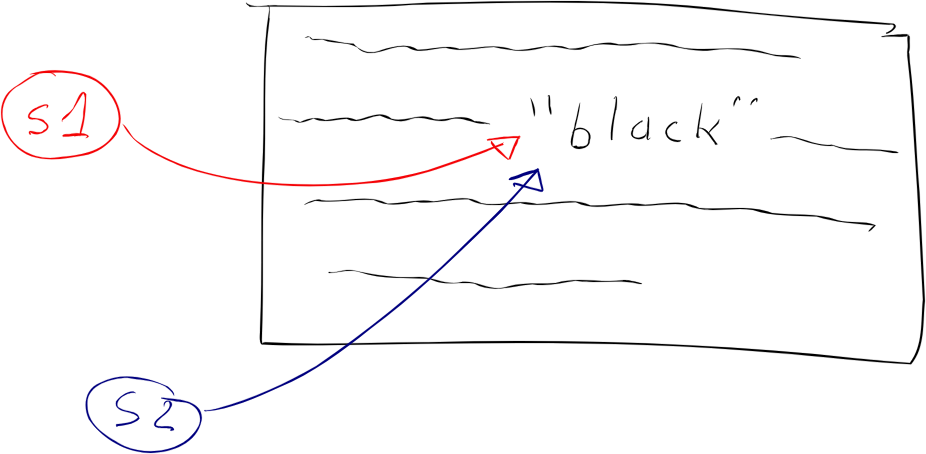

// Number of copies: 1 in rodata, 1 in RAM const char* s1 = "black"; const char* s2 = "black";

But if we change the type to char[], the program will create a copy of the literal when initializing the variables:

// Number of copies: 1 in rodata, 3 in RAM const char s1[] = "black"; const char s2[] = "black";

Likewise, if we change the type to string, the constructor will make a copy of the string:

// Number of copies: 1 in rodata, who knows how many in RAM if you put this in a header const string s1 = "black"; const string s2 = "black";

String Comparison

Now that you've seen some of the quirks of working with such strings on different platforms—and you know how this optimization can be broken—let's look at string comparison using the == operator. Everyone knows that using == on pointer types, including string literals, compares addresses, not content, right?

Two identical string literals can have the same address if the compiler was able to merge them—or different addresses if it wasn’t.

const char* color = "black";

if (color == "black") { // true, string interning

// ...

}

Magic—but it works on the PlayStation.

Everything’s fine… until it’s not—because the moment one of the strings doesn’t get optimized, it all falls apart.

const char color[] = "black";

if (color == "black") { // false

// ...

}

Some might think it’s stating the obvious—but it really can’t be stressed enough: never use the == operator to compare char* strings. And yet, this mistake happens all the time. Just last year alone, I caught six cases (six! In 2024! Four on a Friday, one on Friday the 13th, and two from the same person) where string literals were compared by pointer and caused all kinds of bugs. And about the same number were luckily caught during code reviews.

It seems some people have forgotten that you're supposed to use the strcmp() function, which is part of the standard library and compares characters one by one, returning 0 if the strings match. (It also returns -1 or +1 depending on lexicographical order, but that’s irrelevant here.)

const char color[] = "black";

if (strcmp(color, "black") == 0) { // true

// ...

}

Readability certainly takes a hit—it’s error-prone, and you have to remember how strcmp works—but this is our legacy from plain C, and most people more or less know how to live with it. And of course, performance suffers too, especially on syntactically similar strings.

Not Quite Strings

Ever thought about how memory fragmentation grows when you use lots of string data?

From past experience with regular string and similar types in the Unity engine, total size ended up accounting for 3–6% of a debug build’s memory footprint. Around 3% of that came purely from fragmentation—tiny strings would be deallocated, leaving holes in memory too small to fit anything else. The average size of string data (mostly keys) was between 14–40 bytes, and these little gaps were everywhere. Let’s be honest: 30–60 megabytes of "free memory" on a 1 GB iPhone 5S is more than enough of a reason to optimize it and repurpose that space—say, for textures.

On top of that, these string values aren’t even needed in release builds; they’re only useful for debugging. In fact, the actual string data can be safely stripped from the final builds, leaving only the hashes behind. At the very least, this adds a layer of protection (or at least complexity) for anyone trying to tamper with game resources.

Now add in a linear allocator in a separate memory region, and you can eliminate string-related fragmentation from your build entirely once everything is finalized. Those 6% of test data turn into less than 1% in hashes (just 4 bytes per hash), and we’ll definitely find a good use for the freed-up memory.

xstring color = "black";

xstring color2 = "black"

if (color == color2) { // true

// ..

}

if (color == "black") { // true

// ..

}

On the Tip of Your Fingers

Developers have long come up with different implementations for string interning. When my team integrated this solution into Unity 4, we were inspired by available source code on GitHub and solutions from GCC, but due to open-source licensing constraints, that code couldn’t be directly reused, so we wrote our own. Something similar, I recently came across in the stb library—it was like déjà vu (https://graemephi.github.io/posts/stb_ds-string-interning/).

There are several areas where a lot, a lot, of raw textual data is used, but these strings (which are known in advance) can be hashed: either at runtime or during the content pipeline processing. In the engine, these are prefabs, scene instances, models, and parts of procedural generation. Usually, they are used as independent instances or as templates that can be augmented with other data or components. Other examples include:

Literals hashed in scripts

Tag names in prefabs and scenes

String property values

The idea is quite simple: it’s a basic lookup table that maps identifiers to strings.

namespace utils {

struct xstrings { eastl::hash_map< uint32_t, std::string > _interns; };

namespace strings

{

uint32_t Intern( xtrings &strs, const char *str );

const char* GetString( xstrings &strs, uint32_t id );

bool LoadFromDisk( xstrings &strs, const char *path );

}

}

In the release, during runtime, the engine or game can load a file with hashes and string values if it's required for debugging. In debug builds, strings can be created on the fly directly at the call site. This, of course, is a bit more expensive, but the code remains readable. When we first started integrating this system into Unity, we had a separate object for generating xstring with various masks. This was related to how Unity internally stored string data, and it was more efficient to pre-generate the required identifiers so that they would be stored consecutively, enabling faster processing when needing to iterate through an array of properties. Additionally, in Unity 4, there was a local cache for object components that loaded several subsequent components of an object for more efficient access.

xstring tableId = Engine.SetXString( 'table', 'prop', 0 );

This function led to the creation and hashing of strings like table0prop, table1prop, up to table15prop. It was no longer necessary to separately create table15prop because the engine had already done it. But these are just specifics of how a particular engine was designed, and there's no point in lingering on them, especially since nearly 10 years have passed—maybe they’ve come up with something entirely new by now.

Later, thanks to the simplicity and versatility of this system, I used it with minor variations in other projects and engines. As for the specific implementation, you can take a look at it here (https://github.com/dalerank/Akhenaten/blob/master/src/core/xstring.h). In short, I’ll explain how the code works—it’s actually very simple.

struct xstring_value {

uint32_t crc; // crc

uint16_t reference; // refs

uint16_t length; // size

std::string value; // data

};

class xstring {

xstring_value* _p;

protected:

void _dec() {

if (0 == _p)

return;

_p->reference--;

if (0 == _p->reference)

_p = 0;

}

public:

xstring_value *_dock(pcstr value);

void _set(pcstr rhs) {

xstring_value* v = _dock(rhs);

if (0 != v) {

v->reference++;

}

_dec();

_p = v;

}

...

}

The xstring_value structure stores metadata for a string, and in this specific implementation, std::string was chosen as the storage simply for convenience. In the canonical version, a bump allocator was used, which simply placed a new string at the end of the buffer (it's important to use such xstring structures carefully). This ensured that strings were always alive in memory. The xstring class created a new string (if it didn’t already exist) and stored a pointer to where it was located in memory, or it would retrieve a pointer to an existing copy if the hash matched.

Essentially, these are the main points required for operation—like I said, it's very simple. Below is the code that places a string in the pool. Again, std::map is used for convenience, and honestly, I was too lazy to deal with writing a bump allocator. It only offers a slight performance improvement but a small memory overhead. However, the general approach significantly outperforms standard std::string in terms of creation time when using the system allocator (malloc/new), and in comparison speed as well.

The classic use case for such strings is generating them from scripts and resources, or declaring constant strings in code. If you’ve noticed the xstring class, it has a default comparison operator. Since the class itself is essentially a POD (Plain Old Data) int32_t, all checks boil down to comparing integers. Ten years ago, this provided a performance boost of nearly 30% for animations. Overall, using these strings along with other optimizations made it possible to run Sims Mobile on the iPhone 4S, when the game was originally targeted for the sixth generation and slightly for the fifth. Our overseas colleagues didn’t consider this possible at all.

struct time_tag {

float12 time;

xstring tag;

};

struct events {

static const xstring aim_walk;

static const xstring aim_turn;

};

void ai_unit::on_event(const time_tag &tt) {

if (tt.tag == events().aim_walk) {

ai_start_walk(tt);

} else if (tt.tag == events().aim_turn) {

ai_start_turn(tt);

}

ai_unit_base::on_event(tt);

}

These are some great resources on the topic of string interning. Here's a brief overview of each link:

foonathan/string_id

A C++ library for creating unique identifiers for strings via interning. It maps string literals to unique IDs, which can significantly improve performance when comparing strings or storing many of them.Understanding String Interning

A detailed explanation of string interning, its advantages, and when and how to use it effectively. This article explains how interning works and the trade-offs involved, especially in terms of memory usage and performance.String Interning Blog Post

A blog post discussing the concept of string interning in depth, offering both the theoretical background and practical implications for performance in games and other applications.libstringintern

A C++ library that implements string interning for better memory management. This repository provides a practical implementation of string interning that you can incorporate into your projects.String Interning in C++

An article that focuses on string interning in the context of C++ and Arduino. It explains how string interning can reduce memory usage, improve performance, and is especially useful in embedded systems with limited resources.